An Analysis of Rhythmic Modes in Middle Eastern Music (pre-1600)

Note: These is a class handout that goes along with a class I taught at Pennsic 2001, so it may sound slightly incomplete standing alone.

Visit this page online at: http://www.khafif.com/rhy/rhyhist.html

I focus on "Arabic tradition" -- that is, the culture that grew into

(and later) out of the Arabic empire. This cultural tradition with

it's roots in the caravan and nomadic people and the Islamic religion,

later had deep, long-lasting effects on the cultures of Persia,

Turkey, and North Africa. The Arabic music culture grew from a vocal,

chanted-song tradition of early caravan traders and was tempered (by

academic scholars) with structural analysis of the early Greek musical

traditions. (For more information on this read Farmer [1].)

Challenges in Finding Period Documentation

Even though the Arabic world was a very scholarly place (relatively

speaking) in the middle ages, the academic traditions (especially in

the arts and performing arts) were not so analytical as in

european/western areas. Oral teaching tradition dominated (teachers

did not tend to write about technique), and third-party (audience)

descriptions of musical performances tended more toward the poetic or

evocative, rather than describing technique.

Since it's early roots Islamic culture has taken a schizophrenic view

of music. Listening to music for pleasure has always been a part of

the culture of art and hospitality in the Middle East. However,

during many periods, Islamic law has been interpreted in a way that

proscribed listening to or performing music except in worship of God.

Given this proscription there seems to have been less overlap of

academic scholarship with musical performers than one might expect.

Thus the accounts of musical technique tend toward the philosophical

rather than the practical.

The biggest problem, which affects much period Middle Eastern

research, is that the Monguls sacked the Arabic empire in the mid-13th

century. They focussed on elimination of the upper class and academic

resources; specifically killing scholars and burning libraries. One

notable exception to this purge was, in fact, Safi-al-Din who wound up

working for the Mongul court.

Period Sources

Arabic

-

Ibn Misjab ?-715.

-

-- first known theorist referred to by later authors. No surviving works.

-

Al-KindI (790-874 or 802-866).

-

-- Greek influence.

-- Few surviving works. Mentions names of rhythmic modes, but little

decipherable rhythmic theory.

-

Abu al-Faraj Ali of Esfahan, "KitAb al-Aghani al-Kabir", 10th c.

-

-- one of earliest theory works. Sections on music and rhythm

theory indecipherable.

-

FarabI (872-950), "KitAb al-MusiqI al-Kabir".

-

-- Content about melodic modes, mention of rhythmic mode

names found in later works, but little structural content.

-

Ibn Sina (980-1037)

-

-- More content about melodic modes, still little of rhythm

-

SafI-al-DIn, "KitAb Al-adwar", 1252 and "Risalat al-SarafIya", 1267.

-

-- First decipherable works. Most of known period rhythmic

theory (and much of melodic theory) is found here.

-

QoTb-al-DIn MaHmUd SIrAzI (1236-1311), "Dorrat al-tAj le-Gorrat al-dobbAj"

-

--Persian author essentially repeats SafI-al-Diin.

-

Zayn-al-'AabedIn MoHammad Hosaynii, "QAnUn-e 'elmI wa 'amalI-e mUsIqI", 1500.

-

--again, essentially repeats SafI-al-DIn.

Spanish

-

Alfonso X, el Sabio (1221-1284), "Cantigas de Santa Maria".

-

-- precise specifications for melodic intervals and modes,

but apparently no rhythmic mode or duration notation.

-- There have been attempts at reconstruction (Angles, Higinio) but

many scholars are critical of such work.

Period Transcriptions of Rhythmic Theory

There are four methods found in period Arabic works to represent rhythmic modes.

Poetic Feet

Early Arabic music was based on poetic meter. The first method uses Arabic words

to represent long and short syllables. It is not the meaning of the words that

is important, rather the rhythm in which they would be pronounced.

The Arabic language is based on tri-grams of consonants. Long and

short vowels, prefixes and postfixes modify these trigrams to make

families of words. In Arabic the long vowel is really longer in

duration than the short vowel (this is generally true in English as

well but less important that the sound).

For instance the trigram "K-T-B" involves writing:

- office = maktab (short - short)

- book = kitAb (short - long)

- writer = kAtib (long - short)

- write = kataba (short - short - short)

Notice the variety of long and short syllables.

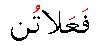

Often the trigram "F-`-L" (means: to do) was used. This type of

mode description was used for music related to poetry. (Syllables that

"end" in a consonant were also considered "long" -- notice: F,', and L

are all "long" sounding consonants.)

It may be that the choice of word breaks indicates phrasing within

the cycle.

Synthetic Syllables

Also complete nonsense syllables were used to represent rhythm.

Typically something like "TAN" for a long syllable and "TA" for a

short. This method was used for non-poetic music and discussion of

pure rhythmic theory. In it's simplest form this method does not

indicate phrasing, however some authors used a different consonants

possibly to indicate this phrasing (mixing "TAN" and "TA" with "NAN"

and "NA") or possibly this was just to make it more pronounceable.

Dot Notation

The third method used was a notation of filled and un-filled dots.

Each dot was a fixed amount of time. Unfilled dots were struck, filled

dots left empty. Note that this method does not differentiate a

musical rest from a sustained note. It also shows no phrasing within

one rhythmic cycle.

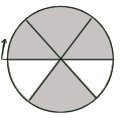

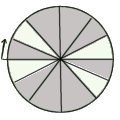

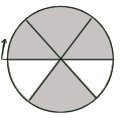

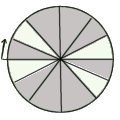

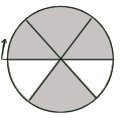

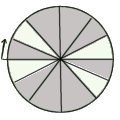

Cycle Notation

The forth method used was a circular depiction of the mode. The

circle was divided into "pie slices". Shaded slices were struck,

un-shaded slices left empty. This is similar to the previous method

but reinforces the cyclic nature of rhythm. We assume that an even

time is given to each slice.

Here is a comparison of a couple of rhythmic modes in each method:

| Mode | hazaj | ramal |

| Poetic | fa-`a-lA-tUn

|

mUf-ta-`i-lA-tUn fa-`i-lUn

|

| Syllabic | ta ta tan tan

ta na nan tan

| tan ta ta tan tan ta ta tan

tan ta na nan tan ta na nan

|

| Dots | o o o . o . | o . o o o . o. o o o . |

| Cycle |  |  |

The Documented Rhythmic Modes

Safi al-Din (via [2]): From the KitAb al-adwAr and Rissalla al-sharafiyya:

al-thaqIl al-awwal 16/8=3+3+4+2+4

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-|

Tt_Tt_Ttt_T-Ttt_|

______T---__T-__| al_aSl (the basis)

________T-__T-__| al-aSl

|

|

|

al-thaqIl al-thAnI 16/8=3+3+2+3+3+2

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-|

Tt_Tt_T-Tt_TT_T_|

T---________T-__| al-aSl

|

|

|

al-thaqIl al-thAnI 8/8

1-+-2-+-|

Tt_Tt_Tt|

|

|

|

khafIf al-thaqIl 16/8=2+2+2+2+2+2+2+2

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-|

T-TtT-TtT-TtT-Tt|

|

|

|

khafIf al-thaqIl 2/4=2+2

1-+-|

T-Tt|

Ttt_| RisAla

|

|

|

thaqIl al-ramal 20/8=4+4+2+2+2+2+2+2+4

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-6-+-|

Ttt-Ttt-T-T-T-T-T-T-Ttt-|

T-________________T---__| al-aSl

|

|

|

al-ramal 12/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-|

T-T-T-T-Ttt-| KitAb

T-T-Ttt-Ttt-| KitAb & RisAla

T---____T---| al-aSl; KitAb

T-Ttt-T-Ttt-| RisAla

Ttt-T-Ttt-T-| RisAla

|

|

|

khafIf al-ramal 10/8=2+3+2+3

1-+-2-+-3-|

T-Tt-T-Tt-|

T______T-_| al-aSl

|

|

|

khafIf al-ramal 12/8=2+4+2+4

1-+-2-+-3-+-|

T-Ttt-T-Ttt-| RisAla

|

|

|

khafIf al-ramal 6/8=2+4

1-+-2-|

T-Ttt-|

|

|

|

muDA`af al-ramal 24/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-6-+-|

Ttt-T-Ttt-T-Ttt-T-Ttt-T-|

T-________________T---__| al-aSl

|

|

|

al-hazaj 12/8=4+3+3+2

1-+-2-+-3-+-|

Ttt-Tt-Tt-T-|

T---____T---|

|

|

|

al-hazaj 6/8=4+2

1-+-2-|

Ttt-T-|

T---T-| al-aSl

Tt-Tt-| RisAla

|

|

|

al-fAkhitI 20/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-|

T---T-T---T---T-T---|

T-T---T---T-T---T---|

T-Ttt-Ttt-T-Ttt-Ttt-| RisAla

|

|

|

al-fAkhitI 28/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-6-+-7-+-|

T-T---T---T---T-T---T---T---| RisAla

T-Ttt-Ttt-Ttt-T-Ttt-Ttt-Ttt-| RisAla

|

|

|

As an indication of how reliable any of this might be, here is a list

of the common modes from al-Kindi (as reconstructed by Farmer via Zonis

[3]). Notice how different they are from the Safi-al-Din versions:

al thaqil al awwal 4/2

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-|

D---D---D---____|

|

|

|

al thaqil al thani 4/2

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-|

D---D---____D---|

|

|

|

al Makhuri 5/8

1-+-2|

DD-D-|

|

|

|

khafif al thaqil 4/8

1-+-|

DDD-|

|

|

|

al ramal 4/4

1-+-2-+-|

D-__D-D-|

|

|

|

khafif al ramal 3/8

1-|

DD|

|

|

|

khafif al khafif 3/8

1-|

D_|

|

|

|

Recall that al-Kindi was significantly more vague than Safi-al-Din

and this reconstruction is suspect. This sort of significant

deviation seems common in all of the very few works that are not derived

directly from Safi-al-Din.

Speculations on Relations to Modern Modes

Here are a couple of comparisons to consider:

period] al-thaqIl al-thAnI 8/8

1-+-2-+-|

Tt_Tt_Tt|

|

|

|

[modern] maqsum 4/4

1-+-2-+-|

DT-TD-T-|

|

|

|

[modern] malfuf 2/4

1-+-2-+-|

D-kT-kT-|

|

|

|

[period] al-fAkhitI 20/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-|

T-T---T---T-T---T---|

|

|

|

[modern] samA`I ath-thaqIl 10/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-4-+-5-+-|

D---T-S---D-D-T-----|

|

|

|

[period] khafIf al-ramal 12/8

1-+-2-+-3-+-|

T-Ttt-T-Ttt-|

|

|

|

[modern] samA`I darij / darj 6/8 or 3/4

1-+-2-+-3-+-|

D-TkT-D-T-__|

|

|

|

Conclusions

For the most part we find that there is little conclusive

documentation on playing style and form of rhythmic modes in early

Middle Eastern music -- but, although we are hampered by conflicting

works, we can make some comparisons to modern modes and speculate on

how those early modes might be related to modern forms.

Bibliography:

-

[1] Farmer, Henry George, "A History of Arabian Music to the XIIIth Century", Luzac and Co LTD, 1929.

-

Little technique information -- lots on history of music, politics, instruments, and musicians. Dense -- a "hard" read.

-

[2] Wright, O., "The Modal System of Arab and Persian Music AD 1250-1300", Oxford University Press, 1978

-

Dense. Lots of highly technical info on melodic modes. Analysis

of some period works. Short summary of rhythmic modes from

Safi-al-Din.

-

[3] Zonis, Ella, "Classical Persian Music, An Introduction", Harvard University Press, 1973.

-

History of Persian music -- mostly from a modern perspective.

Short section on drum history and a short appendix on rhythmic

analysis based on Farmer's analysis of early works.

-

Sachs, Curt, "The Rise of Music in the Ancient World East and West", W.W.Norton and Co, 1943.

-

Quick analyses of history and form of music from many

countries. Short section on the mid-east. Brief summary of ancient

Greek rhythmic modes.

-

During, Jean, "Dawr", Encyclopedia Iranica, vol 7.

-

Dense article on rhythmic cycles and modes -- mostly a historical survey with lists of period authors and mode names.